The multitude of streetcars active on the line came from a multitude of manufacturers. The vast majority of streetcars were powered by overhead electric cables, save the early battery trains, and the self-propelled work trains. The majority of vehicles had automatic emergency breaks, or “dead man’s handles,” where the brake would engage if the motorman were to let go of the handle, potentially due to going unconscious. The novel technology was so exciting to passengers that they would often ask the motorman to let go just to see the system work. Among the approximately 176 cars that would work the line there are a few standouts, both as classes and types, namely passenger, city, freight, combine, and work, as well as a few specific special cars.1

A Trio of Passenger Cars

There were three primary types of passenger cars, produced by a variety of manufacturers. The first type, simply referred to as passenger cars, were dedicated to long distance passenger service on the line. The second, dubbed city cars, were specifically designed for the higher capacity demands of city service, almost exclusively on the Cleveland grid. The third type, called combine, had both passenger seating and space for luggage, packages, and other freight. All three were quite common, and saw use throughout the lines history.234

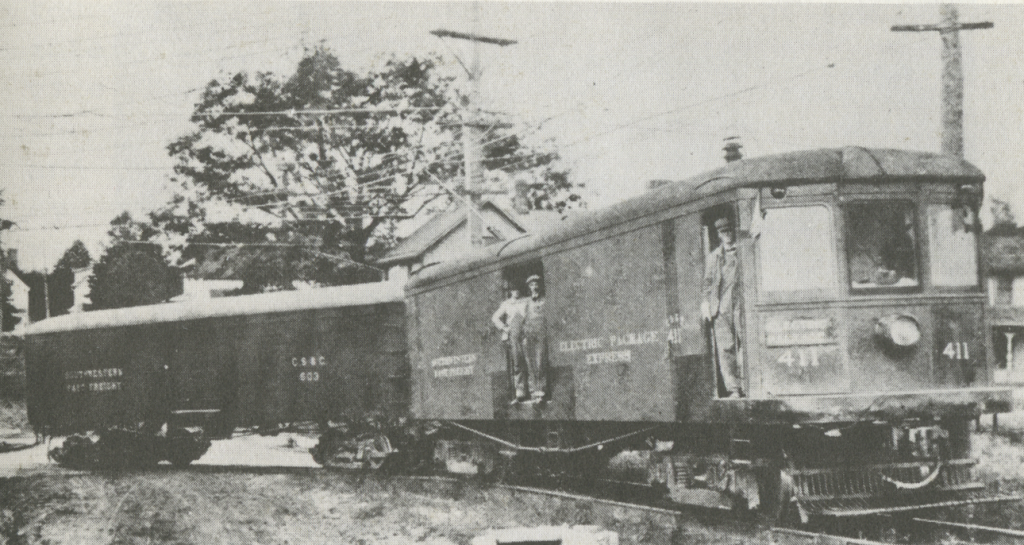

Freight

Entirely separate freight vehicles were much less numerous than combine types, fifteen in total. Mostly box cars in design, they would help drive the strong profit margins of the interurban as a freight corridor. During and post World War I, when couplers were added to the vehicles on the line and heavy freight bans were rescinded, twenty-five freight trailers, many of them rebuilt from other vehicles on the line. The exact number of these that were rebuilt versus brand new is unknown.5

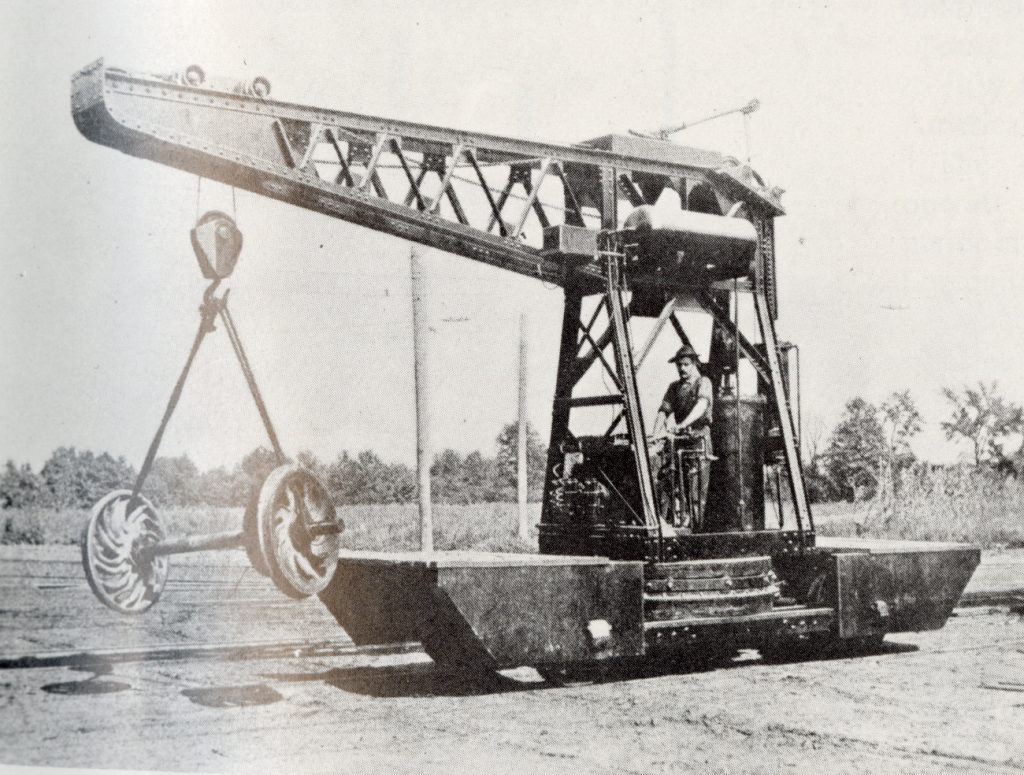

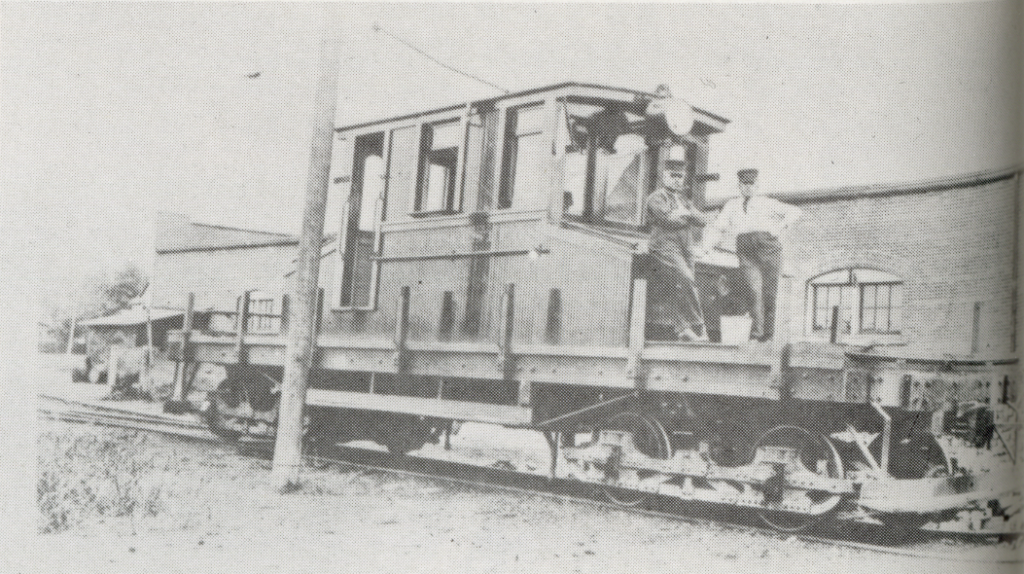

Work Trains

Work trains were affectionately referred to as “Boomers”6 due to being powered by combustion or diesel engines. These vehicles self-propelled nature was key to keeping the interurban running, including recovering from severe storm damage. Numbering twenty-eight in total, they were painted in high-visibility oranges and yellows and provided a number of services. Some were for carrying repair supplies, such as the flat cars and dump cars, while others were built for sweeping and plowing snow. At least one was a crane.7

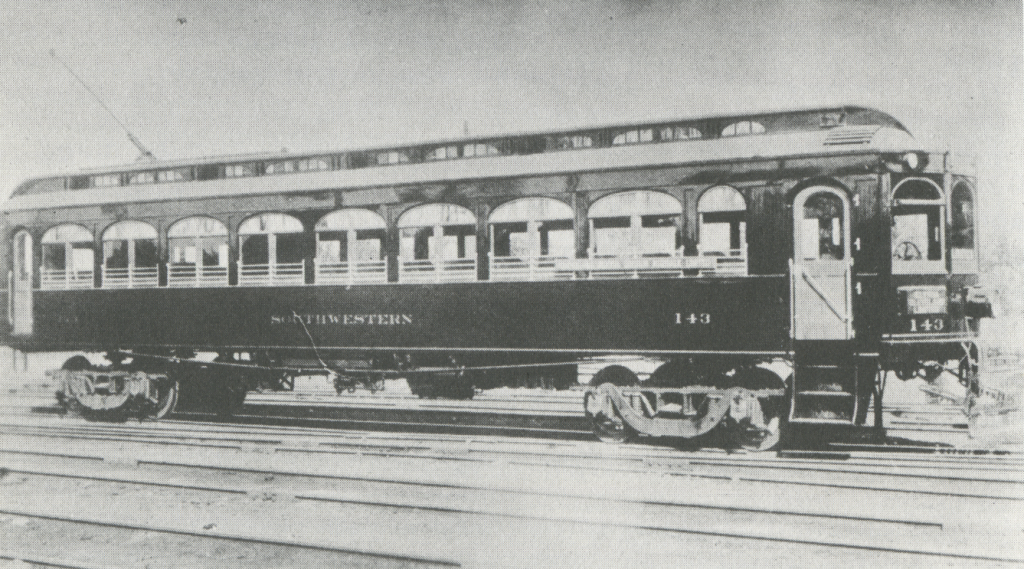

Impressive Capacity

The largest streetcars on the line were the “Muzzleloader Limiteds.” Created by lengthening #130-134 from forty-eight to sixty feet, and #143-149 from forty-five to sixty feet, these, as the name suggests, were front-loading cars designed for Limited services had seventy-two seats and enough standing capacity for seventy more passengers. Complete with a smoking section at the back of the train, these cars represent the Cleveland, Southwestern, and Columbus Railway Company’s reaction to the extreme popularity they experienced for much of their existence.8

A Streetcar Named Dolores

In the author’s opinion, the most important streetcar on the line was #41, better known as “Dolores”. A truly impressive car, Dolores was built to service funerals, carrying grieving families and friends close to the oft-obscure rural cemeteries that many families had burial plots in. It had a compartment with capacity for two coffins, though photo evidence suggests three or more, with rollers on the bottom for easy access, eight elegant wicker chairs for the family along with seating for 28 guests, alongside heating and a restroom. Sources conflict, but Dolores was built of grey oak and was upholstered and draped in either blue or green and purple, both aspects being plush and velvet. According to one source, the car was such an artistic feat that it was exhibited in 11 cities to over 15,000 visitors. Another source attests that Dolores was the only car on the line that was kept truly spotless.910

#41 provided an incredibly popular service that provided unmatched connectivity to families that would have otherwise had to participate in grueling, days-long horse and buggy rides while they were grieving the loss of their family members, a particularly unpleasant sounding combination. In 1916, the service peaked in popularity, with a forty-five trip per month average, perhaps because of World War I. As the interurban began to lose favor, Dolores was retired and unfortunately disposed of via burning.11

First Class

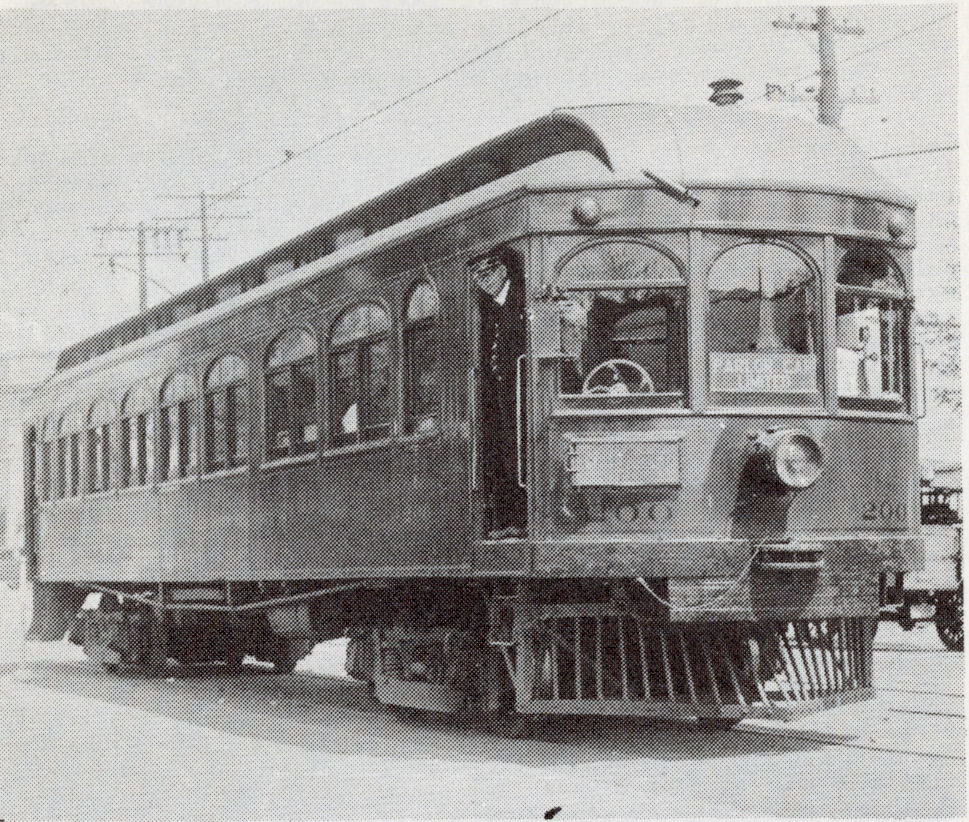

There were two, relatively uncommon types of cars on the line, the Official type and Parlor type. The fanciest cars on the line, save #41 “Dolores”, these cars, which were primarily used in charter services and the so-called “Businessman Special” were comfortable and ornately decorated. The most famous of these was #200, nicknamed “Alvesta.” The first car to be given the moniker “Official”, Alvesta is seen many times throughout photography of the line. Alvesta would later lose its “Official” designation and receive the Parlor designation.121314

Lightweights

A change in car design was actually responsible for the second to last profit the line ever saw. The lightweights, as the name implies, were made of lighter materials and were designed in a sleeker manner. This lowered energy costs significantly, allowing for a profit to be made in 1920, thought their impact was not lasting.15

Decline

Citations

- Brashares, Jeffrey R., and Mable Dillon. The Southwestern Lines: The Story of the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway between Cleveland, Elyria-Oberlin-Norwalk-Wellington-Lorain-Amherst, Berea-Medina-Wooster, Ashland-Mansfield-Crestline, Galion-Bucyrus. S.l.: Ohio Interurban Memories, 1982.

↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Christiansen, Harry. Northern Ohio’s Interurbans and Rapid Transit Railways. Berea Publishing Company, 1965.

↩︎ - Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951.

↩︎ - Brashares, Jeffrey R., and Mable Dillon. The Southwestern Lines: The Story of the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway between Cleveland, Elyria-Oberlin-Norwalk-Wellington-Lorain-Amherst, Berea-Medina-Wooster, Ashland-Mansfield-Crestline, Galion-Bucyrus. S.l.: Ohio Interurban Memories, 1982. ↩︎

- Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951. ↩︎

- Brashares, Jeffrey R., and Mable Dillon. The Southwestern Lines: The Story of the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway between Cleveland, Elyria-Oberlin-Norwalk-Wellington-Lorain-Amherst, Berea-Medina-Wooster, Ashland-Mansfield-Crestline, Galion-Bucyrus. S.l.: Ohio Interurban Memories, 1982. ↩︎

- Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Christiansen, Harry. Northern Ohio’s Interurbans and Rapid Transit Railways. Berea Publishing Company, 1965 ↩︎

- Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951 ↩︎

- Christiansen, Harry. Northern Ohio’s Interurbans and Rapid Transit Railways. Berea Publishing Company, 1965 ↩︎

- Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951 ↩︎

- Brashares, Jeffrey R., and Mable Dillon. The Southwestern Lines: The Story of the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway between Cleveland, Elyria-Oberlin-Norwalk-Wellington-Lorain-Amherst, Berea-Medina-Wooster, Ashland-Mansfield-Crestline, Galion-Bucyrus. S.l.: Ohio Interurban Memories, 1982. ↩︎

- Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951 ↩︎