The majority of the interurban system’s profit was from freight, not passenger service. The near-door-to-door connection and fast, overnight shipping it provided was serious competition for the steam railroads, to the point that the steam railroads successfully lobbied a ban on carrying heavy freight such as steel and ore. This did not stop the interurbans, especially the Cleveland, Southwestern, and Columbus, from making incredible profit in all other areas. The system, according to Max Wilcox, carried “farm produce, [namely] livestock, milk, vegetables, fruit, poultry, [and] eggs, [as well as] small packages, mail, luggage, [and] newspapers.” At its peak, freight service saw fifty carloads each night.1

Milk, News, Beer

There were a few notable freight services on the line. Wellington Creamery, ran three cars a day, every day of the week, for twenty years, an impressive example of the effectiveness of the Southwestern System as a freight corridor. The various newspapers of the region used the line for paper delivery. Max Wilcox recalls avid readers waiting for the train so they could get their copy as soon as possible. Another very popular service on the line, prior to federal prohibition, was the beer delivery service from Cleveland breweries to pubs around the system.

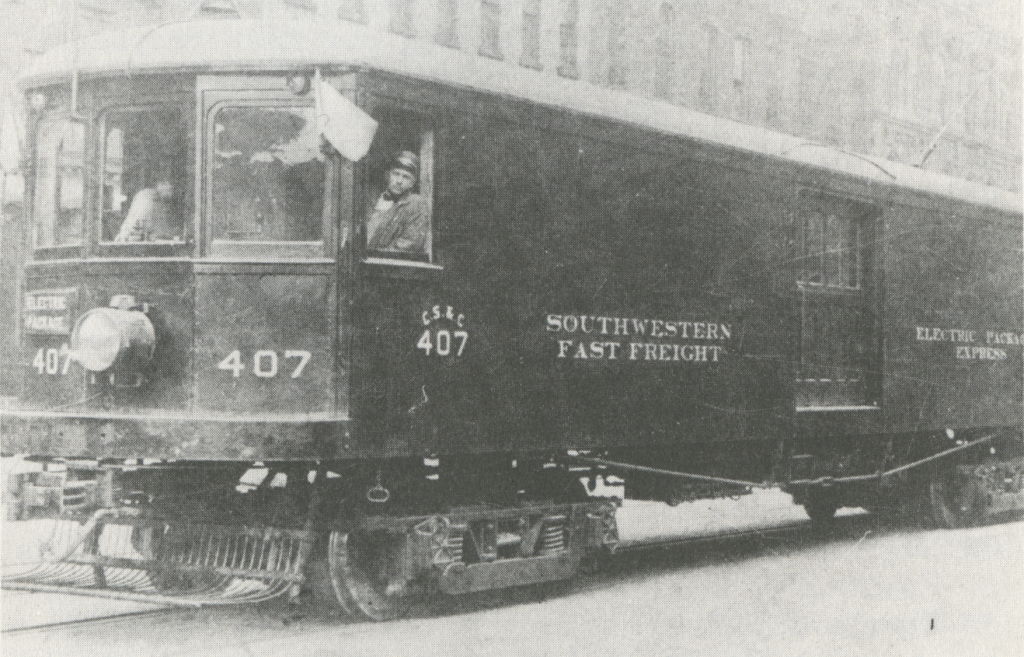

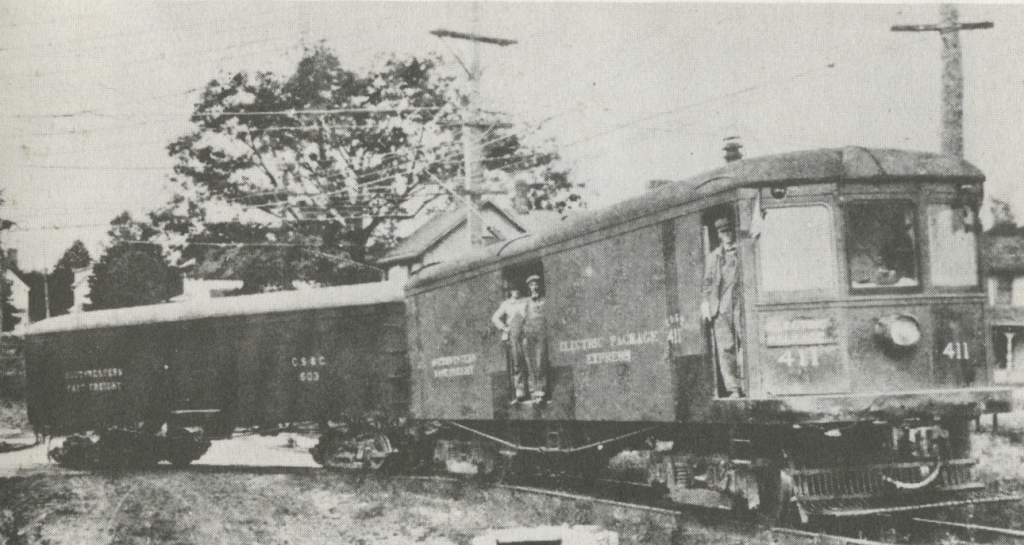

Electric Package Agency

Established on October 1, 1910, the Electric Package Agency was a joint venture between the Cleveland, Southwestern. and Columbus, Lake Shore Electric, Northern Ohio Traction and Light, Cleveland Railway Company, and Cleveland, Painesville, Eastern. Created with the purpose of handling freight in and around Cleveland, it operated across lines over a grand total of 614 miles. The Electric Package Agency was responsible for most freight on the Cleveland, Southwestern, and Columbus, including the previously mentioned milk and newspaper services. These services would be so successful that massive facilities for processing and distribution would be built, much as the world would eventually see for delivery trucks.23

World War I

World War I saw the takeover of the interurban by the United States Federal Government. Besides unbanning the streetcar from heavy freight, they also added coupler systems to many cars. This change would last until the system’s closure.4

Rolling Stock

Citations

- Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951.

↩︎ - Christiansen, Harry. Northern Ohio’s Interurbans and Rapid Transit Railways. Berea Publishing Company, 1965.

↩︎ - Brashares, Jeffrey R., and Mable Dillon. The Southwestern Lines: The Story of the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway between Cleveland, Elyria-Oberlin-Norwalk-Wellington-Lorain-Amherst, Berea-Medina-Wooster, Ashland-Mansfield-Crestline, Galion-Bucyrus. S.l.: Ohio Interurban Memories, 1982.

↩︎ - Wilcox, Max E. The Cleveland, Southwestern, & Columbus Railway Story. Vol. 1. 1 vols. Max E. Wilcox, Northern Ohio Railway Museum, 1951. ↩︎